North Sea Crossings: family audio highlights

Take a tour around the exhibition with Anne Louise Avery and Steve Pratley. Learn about the objects on display, Reynard the Fox and his friends and a little Dutch on the way.

You are welcome to use your device with or without headphones in the gallery.

To navigate to the audio track, scan the QR codes in the gallery or scroll to the relevant stop on the page. Stops are marked with a headphones icon ( ).

Transcripts of each stop are available.

Introduction

Audio transcripts

Look at this magnificent view of London! Bustling, smelly, noisy, violent, vibrant, wonderful London! Now, this is an imaginary London, made by an artist called Claes Jansz Visscher, who lived in Amsterdam and only really visited the city in his mind.

But, still…listen closely and you can almost hear all the sounds of the great city: the splashing from the waterwheels by London Bridge, dogs barking, dogs howling, geese honking, the shaking of dice in a tavern game, the pull of oars of the river boats, the clapping and booing at the theatres, the ringing of church bells, the sloshing of dirty water on the streets, people chatting and shouting and screaming and laughing and fighting and playing and being silly like people always have been.

And look, you might be able to see someone going to buy a book from a shop at the sign of the Gilded Cup in Fore Street. What book are they buying? It’s a best seller! The history of Reynard the Fox – translated from the Dutch by William Caxton. Everyone loves the stories of Reynard in London – he suits the city – wild and wicked and funny and always, always in trouble with authority!

The word for the first exhibit this object on our tour is City – or in Dutch – Stad.

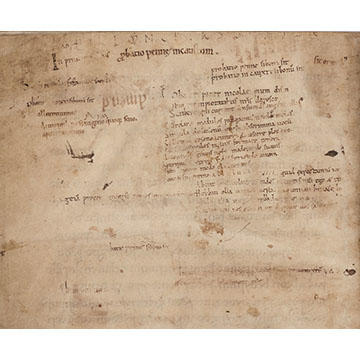

Study the ancient, faded writing of Exhibit Two this object. Are these spells or incantations? Not quite.

Imagine, if you will, a sunny Thursday afternoon in the spring of 1075, or thereabouts.

The place is Rochester Priory, by the banks of the swift-flowing river Medway in Kent.

A monk is cutting the nib of his new quill. A feather from a goose, perhaps, or even a swan. He needs to try out the nib before writing anything really important, so he dashes out the usual sort of thing - “testing this pen”, “testing this ink” etc.

And you can still see them, on the page right there, near the top, in Latin, and a little further down, in Old Dutch. Little did that monk know, of course, that one thousand years later, his quick throwaway tester sentences would be wondered at by thousands of people, including you right now!

In the Bodleian retelling of Reynard the Fox, Reynard’s wife, the kindly and clever vixen Hermeline, is also a scribe like our monk. Her paws are always covered in ink and her mind is always on her work. She writes in Latin too, but also Middle Dutch, and she loves to translate Arabic texts, of which there were many, many important ones in the Medieval World.

The word for this item, is, of course, Pen, which is the same in Dutch, Pen. It originally comes from the Latin for long feather – Penna.

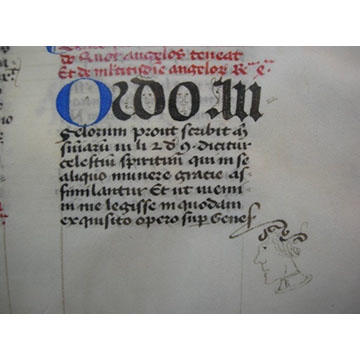

If you’ve ever doodled in an extremely dull lesson or an endless meeting or a late afternoon lecture in the depths of winter, then you know exactly how the fifteenth-century scribe Theoderic Werken felt.

The year was 1448 and Theoderic had been given a new job – a mammoth job transcribing or copying six huge volumes of a Latin encyclopaedia. This was a very important job for a very, very important client, one William Gray, former Chancellor of Oxford University, future bishop of Ely. From when he was a young boy, Gray loved books and at Oxford and on his travels around Europe, he paid scribes handsomely to make copies of manuscripts for his library.

So, Theoderic was half-way through the first exceedingly long volume, when he drew a rather worried looking face in the margin. Was it him? A self-portrait? I like to think so. I wonder if William Gray chuckled to himself when he came across it!

Theoderic loved drawing cartoon people, and you can find all manner of faces all over his books. Today, he would probably work as a cartoonist or an animator. Perhaps he’d even work for Aardman!

In Reynard the Fox, King Noble the Lion, ruler of all Flanders, is notoriously short of attention. He never really listens to his subjects and their concerns, and drifts off every time Sir Tybert the Cat or one of his other advisors starts to talk about important matters of state.

He likes to think about jousts and food and squashing his enemies and that’s about it. If he ever had to do any writing, he would certainly spend most of his time doodling in the margins too.

The word for this object is Doodle or Krabbel in Dutch.

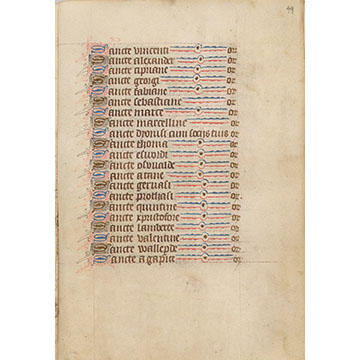

Saints are very important in medieval times, not least in Flanders. There are dozens upon dozens of saints in Reynard the Fox. I

n the Bodleian version, the animal characters mark the changing seasons by Saints’ days and festivals and celebrations, they light candles to them, implore them for help in their adventures and misadventures, make very long and, sometimes perilous, journeys to their shrines and organise vastly expensive festivals to celebrate their holy days. Reynard’s arch-enemy, Baron Isengrim the Wolf even has a book of Saints’ Stories which he flashes around the court and pretends to read.

Reynard the Fox’s chapel in his castle of Malperduys is dedicated to the Patron Saint of Hunters, Saint Hubert. And one of Reynard’s most precious belongings is a sacred relic - one of Hubert’s mummified toes! Reynard is very proud of this grisly artefact and insists on showing it to everyone who comes to visit.

In the Book of Hours in the case, can you spot the name of Saint Walleparde? He was a completely imaginary saint – conjured up from a Flemish scribe’s mistake in copying an English name. No one ever prayed to him. No one ever held a party in his name.

Unseen saints shaping the world of Reynard the Fox, and a saint who didn’t even exist, a phantom saint hovering at the margins of 15th century books. All a little spooky.

And so, the word for this object is Ghost or Spook in Dutch.

In the Flemish language of Reynard’s time, they also used to say “ghost” with a “gh” – William Caxton, translator of Reynard, brought the spelling over from Flanders, and we’ve used it in English ever since!

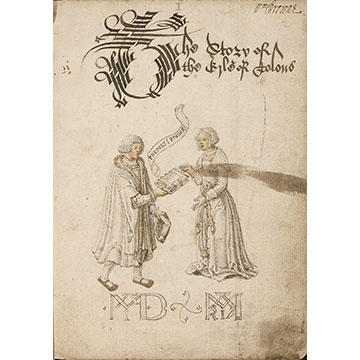

Look at the elaborate and very, very fancy drawing of a gentleman presenting his lady, Maid Maria, with the very book itself. A long-long-long forgotten love affair preserved only in a single sketch.

The stories of Reynard the Fox are filled with romance and romantic intrigue too.

Reynard adores his wife, Hermeline, but also has a great forbidden love for a former sweetheart, Lady Erswynde the She-Wolf, the poor ill-treated wife of his enemy Isengrim the Wolf.

Whether that love was pure and noble and knightly, or treacherous and abusive and a terrible betrayal of his marriage and everyone and everything he holds dear, we are never absolutely sure. Could go either way with Reynard, to be quite honest.

On the other paw, Reynard’s best friend, the loyal and sensible and kindly Grimbart the Badger, lost his beloved sweetheart to a horrible lung-fever when they were both young, and has remained a bachelor in her honour ever since.

He is one of most quietly romantic characters in the Bodleian retelling of the fox epic, and this exhibit, a charming and elegant gift, would have moved that sentimental old badger to tears.

The word for this case is Love or Liefde

William Caxton was the very first English printer, working at the cutting-edge of technology. He produced the first printed book in English, made in Ghent in Flanders.

The impact of printing in 15th century Europe utterly transformed society and access to knowledge, much as the internet would in the late 20th century, and it was Caxton who introduced that extraordinary new process to England, after learning about it in Cologne in Germany.

Caxton was born in the Weald of Kent, but spent most of his life in Flanders, selling fine cloth in the busy trading cities of Bruges and Ghent, and he knew the stories and the landscapes of Reynard the Fox, the wild and watery world of the Waasland in the east of the country, as well he knew the bluebell woods and the downlands of his English childhood.

When he returned to England in 1476, he set up a printing press in Westminster Abbey under the famous sign of the red Pale (which was literally, a wooden shield with a red painted band on it – a knightly sort of symbol. Early printers liked that sort of thing as their shop signs).

Caxton knew exactly the sort of stories which would sell – fairy tales and adventures and exciting battles - Chaucer, the tales of Troy, and of course, the history of Reynard the Fox – the great Fox epic – which he published in the summer of 1481. It was an instant hit. A best seller.

Everyone in London was exhausted by war and politics, they just wanted to laugh and to root for this outrageously untruthful and shockingly naughty outsider fox, a fox who could escape from the trickiest of traps and outmanoeuvre a king with nothing but his wits and his skill in spinning a tale.

The word for this exhibit object is Printing Press or in Dutch, De Boekdrukkunst.

Here we’ve reached the Reynard case.

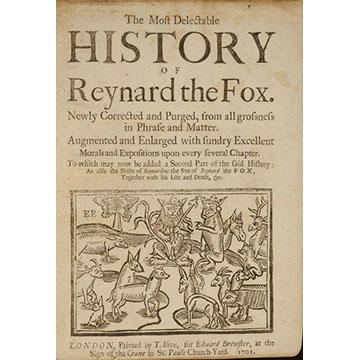

Look at the illustration. It’s almost four hundred years old!

Can you make out the name of the printer – Elizabeth Allde, who ran her business by the great south door of Greyfriars church, attached to the Christ’s Hospital in London.

Women were active in the early book trade as printers, booksellers and writers and Elizabeth published all manner of books, including this richly illustrated copy of Reynard.

The picture shows King Noble the Lion and his wife, Queen Gente the Lioness, holding court in their castle in the fine city of Ghent in Flanders.

Milling around them are their courtiers, all come to complain bitterly about the antics of Reynard the Fox. He’s been stealing and murdering and lying and terrifying animals up and down the land, and everyone has had enough. After a great deal of chat and a great deal of damning evidence, King Noble sends the bumbling bear, Sir Bruin, all the way to Reynard’s fortress in the river town of Rupelmonde to drag him to court to be tried for his terrible crimes.

However, Reynard tricks Bruin into getting stuck, Winnie the Pooh fashion, whilst searching for honey in a tree trunk, and escapes a free fox, yet again.

And the word for this object is Fox or Vos in Dutch.

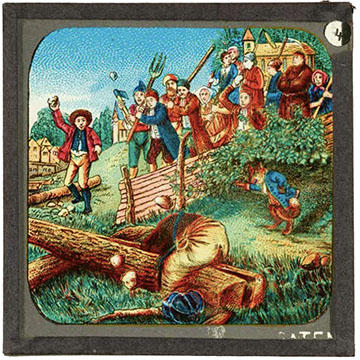

Christmas, 1896. There’s a sharp frost across Oxford and everything feels very festive.

Just down the Broad from the Bodleian, a great treat at Balliol College is about to take place – a magic lantern entertainment for 120 children – including, perhaps, slides just like these, depicting the old Flemish tales of Reynard the Fox! Jewel-coloured pictures of Reynard and Grimbart the Badger and Cuwaert the Hare and Bruin the Bear and Hermeline the Vixen and Tybert the Cat – vast and colourful as stained glass.

Magic Lantern Shows like this were the cinemas of the 19th century, usually accompanied by a storyteller (a Mr Timms at Balliol) to introduce each slide, they let you escape into magical lands and adventures and taught you all about the world and its doings.

The first magic lanterns were created in the 17th century, invented by the Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens. Many of the early slides were very scary, designed to terrify their viewers, and the viewing device was sometimes called “the lantern of fear”.

One of the earliest set of pictures, designed by Huygens in 1659, shows a figure of Death as a skeleton removing his head and then putting it back on again!

And the word for this object? Lantern – in Dutch, Lantaarn.

Reynard the Fox is one of the world’s most famous tricksters, the direct ancestor of Roald Dahl’s Fantastic Mr Fox.

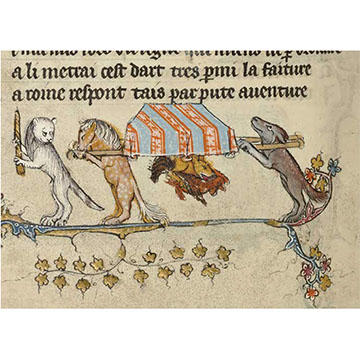

He is a genius at deception, even when he’s supposed to be dead. Can you see the illustration in the margins of the manuscript?

It depicts Reynard’s funeral – an extremely sad occasion. Even his sworn enemies are pretending to be upset – the dastardly Isengrim the Wolf is carrying his bier or funeral stretcher with the snooty Sir Ferrant the Horse, whilst King Noble the Lion and Tybert the Cat, lead the sombre procession.

But Reynard isn’t dead, far from it, it’s just another sneaky ruse, and you can see him slipping out from under his fancy velvet pall with another funeral guest, Sir Chanticleer the Cockerel, in his jaws – a cunning escape and a tasty chicken supper in one fell swoop!

The word for this object is trickster – Schurk or Bedrieger in Dutch.

The story of Reynard, the trickster fox, stretches all the way back to the Ancient Greek fables of Aesop, but his first named appearance - his first big role in medieval literature was in 1149, almost 900 years ago, in a very long Latin poem about Isengrim the Wolf written by a monk in the city of Ghent.

From that moment on, Reynard lopes around Europe popping up in stories in France, Germany, the Low Countries, Italy, Britain…In fact, he becomes so popular in France, that the word for fox eventually changed permanently from the old name goupil to renard.

In 1481, Caxton publishes his best-selling version and in 1792, the famous German philosopher Johann Wolfgang von Goethe starts writing his poem about the fox in the middle of a raging battle. He was a bit fed up with war and needed a good chuckle, he said afterwards.

Century after century, dozens upon dozens of books and writers and illustrators, right up until today, with our very own Bodleian version. And the word here is Book or Boek in Dutch.

Some of these hundreds of books are displayed in the case. Many of the Reynards look very sweet and charming, others you certainly wouldn’t want to meet in a dark forest at night. Have a look at all the covers. What kind of Reynard would you write about – a dashing trickster or an evil murderous wretch.

Here we have a curious object which recounts a very strange tale of giants and of the very beginnings of both Britain and Holland. How close our links really are in the magical world of myth and fairy tale.

Back before they were any cities or villages or roads or even people living in Britain, they were giants. It was their land and they called it Albion. One day, a grizzled old Trojan warrior called Brutus lands on the coast of Devon, defeats and banishes the giants and renames their country after him: Britain.

The poor giants become exiles, sailing across the grey North Sea to start a new life – the very first inhabitants of a new land – Holland.

But where are the giants in the picture, you may ask? Well, printers were very resourceful back then, and this particular printer from the city of Leiden decided to reuse an image of the magician Merlin from the King Arthur tales instead of commissioning a new one for his short story of giants.

It sort of fits in a vague sort of way – Merlin looks rather tall and impressive and those are some pretty scary-looking dragons fighting behind him. And King Arthur, of course, is also a figure closely related to the very formation of Britain.

So, in honour of this wonderful muddle of legends, the word for this exhibit, our last exhibit, object is Dragon, or in Dutch, Draak – both originating from the Latin Drako, which you’ll know from Draco Malfoy in Harry Potter.