History of the Bodleian

Introduction

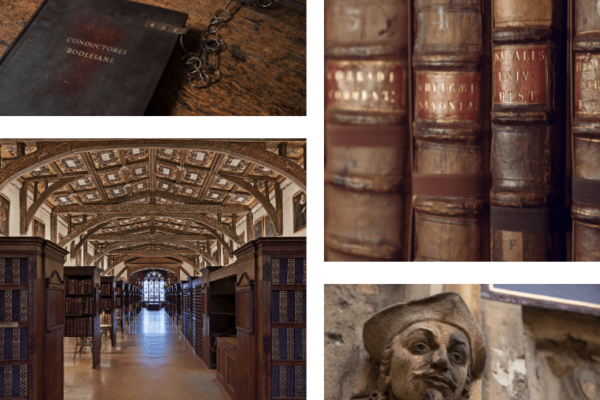

Oxford’s libraries are among the most celebrated in the world, not only for their incomparable collections of books and manuscripts but also for their buildings, some of which have remained in continuous use since the Middle Ages. Libraries in the Bodleian Libraries group include major research libraries; libraries attached to faculties, departments and other institutions of the University; and, of course, the principal University library – the Bodleian Library – which has been a library of legal deposit for 400 years.

The Bodleian Library is one of the oldest libraries in Europe, and in Britain is second in size only to the British Library. Together, the Bodleian Libraries hold over 13 million printed items. First opened to scholars in 1602, it incorporates an earlier library built by the University in the 15th century to house books donated by Humfrey, Duke of Gloucester. Since 1602 it has expanded, slowly at first but with increasing momentum over the last 150 years, to keep pace with the ever-growing accumulation of books, papers and other materials, but the core of the old buildings has remained intact.

Known to many Oxford scholars simply as ‘the Bod’, these buildings are still used by students and scholars from all over the world, and they attract an ever-increasing number of visitors.

Early history

The University’s first purpose-built library was begun in approximately 1320 in the University Church of St Mary the Virgin, in a room which still exists as a vestry and a meeting room for the church. The building stood at the heart of Oxford’s ‘academic quarter’, close to the schools in which lectures were given. By 1488, the room was superseded by the library known as Duke Humfrey’s, which constitutes the oldest part of the Bodleian.

Humfrey, Duke of Gloucester and younger brother of King Henry V, gave the University his priceless collection of more than 281 manuscripts, including several important classical texts. The University decided to build a new library for them over the new Divinity School; it was begun in 1478 and finally opened in 1488.

The library lasted only 60 years; in 1550, the Dean of Christ Church, hoping to purge the English church of all traces of Catholicism including ‘superstitious books and images’, removed all the library’s books – some to be burnt. The University was not a wealthy institution and did not have the resources to build up new collections. In 1556, the room was taken over by the Faculty of Medicine.

Thomas Bodley

The library was rescued by Sir Thomas Bodley (1545–1613), a Fellow of Merton College and a diplomat in Queen Elizabeth I’s court. He married a rich widow (whose husband had made his fortune trading in pilchards) and, in his retirement, decided to ‘set up my staff at the library door in Oxon; being thoroughly persuaded, that in my solitude, and surcease from the Commonwealth affairs, I could not busy myself to better purpose, than by reducing that place (which then in every part lay ruined and waste) to the public use of students’.

In 1598, the old library was refurbished to house a new collection of around 2,500 books, some of them given by Bodley himself. A librarian, Thomas James, was appointed, and the library finally opened on 8 November 1602.

Bodley’s work didn’t stop there. In 1610 he entered into an agreement with the Stationers’ Company of London under which a copy of every book published in England and registered at Stationers’ Hall would be deposited in the new library. This agreement pointed to the future of the library as a legal deposit library, and also as an ever-expanding collection that needed space. In 1610–12 Bodley planned and financed the first extension to the medieval building, known as Arts End.

Bodley died in 1613, shortly after work started on his planned Schools Quadrangle. These buildings were designed to house lecture and examination rooms (‘schools’ in Oxford parlance) to replace what Bodley called ‘those ruinous little rooms’ on the site, in which generations of undergraduates had been taught. In his will Bodley left money to add a third floor designed to serve as ‘a very large supplement for stowage of books’, which also became a public museum and picture gallery, the first in England. The quadrangle was structurally complete by 1619, though work continued until at least 1624.

The last addition to Bodley’s buildings came in 1634–7, when another extension to Duke Humfrey’s Library was built; it is still known as Selden End, after the lawyer John Selden (1584–1654) who made a gift of 8,000 books. The library was now able to receive and house numerous gifts of books and, especially, manuscripts. It was these collections that attracted scholars from all over Europe, and the library still opens its doors to scholars from around the world.

Another tradition, still zealously guarded, is that no books were to be lent to readers; even King Charles I was refused permission to borrow a book in 1645. But with no heating until 1845 and no artificial lighting until 1929, the number of users should not be overestimated; in 1831 there was an average of only 3–4 readers a day, and the Library only opened from 10am–3pm in the winter and 9am–4pm in the summer.

18th–19th centuries

The growth of the collection slowed down in the early 18th century, but the late 17th and early 18th centuries saw a spate of library-building in Oxford. The finest of all the new libraries was the brainchild of John Radcliffe (1650–1714). He left his trustees a large sum of money with which to purchase both the land for the new building and an endowment to pay a librarian and purchase books. The monumental circular domed building – Oxford’s most impressive piece of classical architecture – was built between 1737 and 1748 based on the designs of James Gibbs, and it was finally opened in 1749. For many years the Library, as it was called until 1860, was completely independent of the Bodleian.

Meanwhile the Bodleian’s collections had begun to grow again; more effective agreements with the Stationers’ Company, purchases and gifts meant that, by 1849, there were estimated to be 220,000 books and some 21,000 manuscripts in the library’s collection. The Bodleian also housed pictures, sculptures, coins and medals, and ‘curiosities’ (including a stuffed crocodile from Jamaica).

By 1788, the rooms on the first floor were given over to library use, and by 1859 the whole of the Schools Quadrangle was in library hands. This left more space for storing books, which was further increased in 1860, when the Radcliffe Library was taken over by the Bodleian and renamed the Radcliffe Camera (the word camera means room in Latin).

20th century and the New Library

By the beginning of the 20th century, an average of a hundred people a day were using the library; the number of books had reached the million mark by 1914. To provide extra storage space, an underground book store was excavated beneath Radcliffe Square in 1909–12; it was the largest such store in the world at the time.

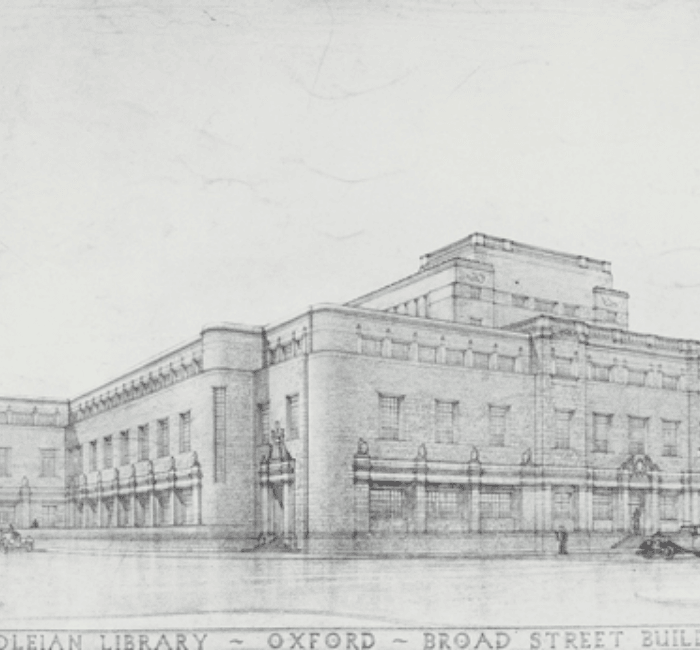

But with both readers and books increasing, the pressure on space once more became critical. In 1931 the decision was taken to build a new library, with space for 5 million books, library departments and reading rooms, on a site occupied by a row of old timber houses on the north side of Broad Street. The New Bodleian, as it was known then, was designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott and went up in 1937–40.

In 1975 new office space was acquired in the Clarendon Building, built for the University Press in 1712–13, and occupying the crucial site between the Old and New Libraries. Thus the whole area between the Radcliffe Camera and the New Library – the historic core of the University – came into the hands of the Bodleian.

Most recently, the New Bodleian building was completely renovated and reopened with large public and new academic spaces as the Weston Library in 2015.

For more information, please see our History of the Bodleian illustrated brochure (PDF).

Further reading

£12.99

A Brief History of the Bodleian Library

£6

Bodleian Library

Souvenir Guidebook

£30

New Bodleian –

making the Weston Library

£12.99

Dr Radcliffe's Library