Gifts and Books

About the exhibition

The giving and receiving of gifts is fundamental to human societies.

Drawing on material from ancient Sumerian writing tablets to contemporary fiction for children, Gifts and Books will explore the importance of gift-giving through books and across time, and how this apparently simple act reveals wider interactions, relationships and belief systems.

Generosity. Power. Reverence. Love. Struggle. Obligation.

Come and explore the meaning of gifts, exchange and the stories we tell about them.

Curator

This exhibition was curated by Dr Nicholas Perkins, Associate Professor and Tutor in English, St Hugh's College, University of Oxford

Audio highlights

Listen to a selection of academics and authors discuss the role of giving and receiving in objects from a medieval text to contemporary children's fiction.

Listen in the gallery using the QR codes, or at home.

Object highlights

Ormesby Psalter, 14th century

Percy Bysshe Shelley's guitar

Book of Hours (England, 16th century)

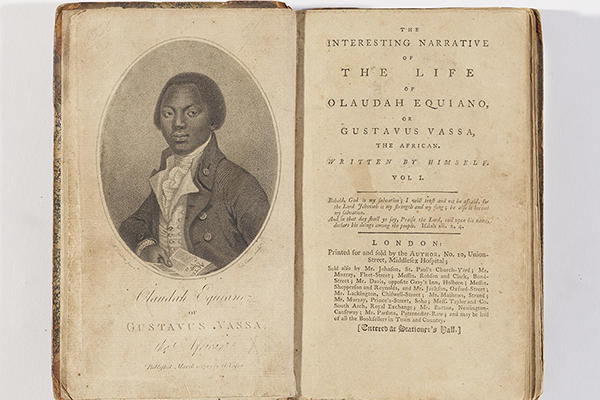

'The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano' (1789)

In the shop