Locke Unlocked

Locke Unlocked: A Look at John Locke’s An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

19 February – mid-April 2022

This display is now closed

This display pays tribute to philosopher John Locke's An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689) by offering a new way to explore a revered text.

Six central ideas in the Essay are elucidated using (mostly) paired objects. The six vignettes show three dimensional models that ask the viewer to consider enduring philosophical problems. Pairs of objects provide a powerful language to explore theories, highlight distinctions, and provoke philosophical thinking.

The objects in the display are at once things, models of things, and models of ideas.

About the artist

Cliff Landesman, the creator of Locke Unlocked, first read Locke's Essay as a student at University College, Oxford. He holds an MA from Oxford University and a PhD from Princeton University. He is currently an origami designer and teacher, living in Burlington, Vermont, USA.

Explore the ideas

Explore Locke's central ideas and listen to audio commentary on each by philosophers Tim Crane and Peter Millican.

Let us suppose the mind to be, as we say, white paper void of all characters, without any ideas. How comes it to be furnished? Whence comes it by that vast store which the busy and boundless fancy of man has painted on it with an almost endless variety? Whence has it all the materials of reason and knowledge? To this I answer, in one word, from experience

Book II, Chapter 1, 2

How does knowledge begin? Locke offered us a vivid metaphor: a blank white page. Our minds start out as a blank white page with no preconceived notions, no prior ideas; nothing is yet inscribed on the white page. What starts the process of acquiring knowledge? Locke answered with one word: experience.

We are certainly born with appetites and capacities (such as the capacity to perceive, to learn, or to acquire a language). Locke did not deny these sorts of inherited capacities. Rather, he rejected the stronger claims of previous thinkers, such as Plato and Descartes. They argued that we start out with certain concepts or principles, either implanted in us by God, or remembered from a previous life. For Locke, all that we know is grounded in experience. As he put it, “no ideas are innate”.

Audio commentary

Listen to audio commentary by philosophers Peter Millican and Tim Crane, with Locke's words read by Victoria Jenner.

Download the accompanying transcript for the no innate ideas audio commentary (Word document)

Suppose a man born blind, and now adult, and taught by his touch to distinguish between a cube and a sphere… Suppose then the cube and sphere placed on a table, and the blind man to be made to see: quaere, whether by his sight, before he touched them, he could now distinguish and tell which is the globe, which the cube?

Book 2, Chapter 9, 8

After the first appearance of An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, William Molyneux wrote Locke a letter. In the letter, Molyneux proposed an ingenious thought experiment. Locke was so taken with Molyneux's thought experiment that he wrote about it in the second edition of the Essay. The passage quoted above is Locke quoting from Molyneux’s letter.

Soon after, philosophers started debating Molyneux’s problem.

Gottfried Leibniz, a contemporary of Locke’s, argued that (given certain assumptions) the blind person would be able to identify each object. After all, a cube has edges, while a sphere is uniform. A newly sighted person would be able to see edges and uniformity, allowing the person to say which object is the cube and which is the sphere. Locke and Molyneux were not convinced.

Molyneux’s question remains alive today, over 300 years later, even though scientific research has greatly improved our understanding of the development of human sensory systems. The problem has been called, “one the most fruitful thought-experiments ever proposed in the history of philosophy”.

Image credit: Cliff Landesman

Audio commentary

Listen to audio commentary by philosophers Tim Crane and Peter Millican, with Locke's words read by Victoria Jenner.

Download the accompanying transcript for the Molyneux’s problem audio commentary (Word document)

Qualities thus considered in bodies are:

First, such as are utterly inseparable from the body… These I call original or primary qualities of body; which I think we may observe to produce simple ideas in us, viz. solidity, extension, figure, motion or rest, and number…

Secondly, such qualities which in truth are nothing in the objects themselves but powers to produce various sensations in us by their primary qualities, i.e. by the bulk, figure, texture, and motion of their insensible parts, as colours, sounds, tastes, etc.

Book 2, Chapter 8, 9–10

Tops spin or rest motionless in place. They are long or short in length. Many have a round shape. These are properties of tops and other physical things.

Locke thought that these kinds of properties, such as motion, size, shape, and number, are primary: they are inherent in the objects.

A colour wheel, on the other hand, has segments with different colours. Some segments might be red, and others green or blue. Locke thought these kinds of properties, such as colour, taste, smell, and sound, are secondary: they depend on a person’s subjective sensory experience.

For Locke, secondary qualities, while real properties of an object, are not inherent in the objects. Rather, secondary qualities are powers an object has to produce certain sensations in us. A sharp needle may prick us and cause us pain. We say the needle is painful, but we don’t think being painful is an inherent property of the needle. Needles merely have the power to cause us pain.

Locke thought colours were like being painful and unlike being round.

Image credit: Cliff Landesman

Audio commentary

Listen to audio commentary by philosophers Tim Crane and Peter Millican, with Locke's words read by Victoria Jenner.

Download the accompanying transcript for the primary and secondary qualities audio commentary (Word document)

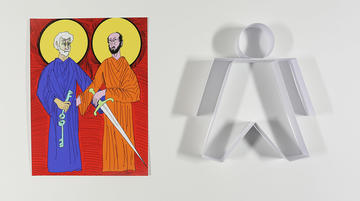

...let anyone reflect and then tell me wherein does his idea of man differ from that of Peter and Paul… but in the leaving out something that is peculiar to each individual...

Book Three, Chapter Three, 9

We interact with individual people. We live in an apartment or a house. We are familiar with the city where we reside. These are all particular things: this person; this building; this city.

But we also know and talk about general things. We say that “people don’t live forever”, “buildings need maintenance”, and “cities have streets”. Almost every noun is a general term. These general terms (“person”, “house”, “city”) are the basic building blocks of many of our thoughts.

What are these general terms and how do we acquire them?

Locke offered us a theory about general concepts (or “abstract ideas” as he called them). Locke’s theory is that we start with particular concepts (such as the individuals Peter and Paul) and we subtract what is unique to each of them. What remains are the properties they share in common. The general concept of a “human being” (a “man” as Locke put it) is set by these core properties. Both Peter and Paul have two legs. Both have faces. Both speak a language.

Whatever properties all humans share, that is the meaning of “human being”. For Locke, we arrive at abstraction by subtraction.

Audio commentary

Listen to audio commentary by philosopher Peter Millican, with Locke's words read by Victoria Jenner.

Download the accompanying transcript for the abstract ideas audio commentary (Word document)

...the nominal essence of gold is that complex idea the word gold stands for, let it be for instance a body yellow, of a certain weight, malleable, fusible, and fixed. But the real essence is the constitution of the insensible parts of that body on which those qualities and all the other properties of gold depend.

Book Three, Chapter 6, 2

Real gold is different from fake gold. For someone buying a ring, it matters whether the ring is made from gold or from something that merely looks like gold. Today, we know that gold is a pure element, with 79 protons. Fake gold is made from a combination of other elements. It can look and feel like gold, but is not real gold. It is an imitation.

Locke did not know that the atomic nuclei of gold have exactly 79 protons. So he did not know what gold really is. However, he could have pointed to a piece of gold and said: "Whatever has the same fundamental nature as this, I will call, ‘real gold’. Whatever merely looks and behaves like this, I will call, ‘imitation gold’."

Some contemporary philosophers believe that we can discover from experience a thing’s necessary properties. Long after Locke wrote his Essay, scientists discovered the atomic nature of gold – what Locke would have called its real essence.

Image credit: Cliff Landesman

Audio commentary

Listen to audio commentary by philosopher Tim Crane, with Locke's words read by Victoria Jenner.

Download the accompanying transcript for the substance and substratum audio commentary (Word document)

...should the soul of a prince, carrying with it the consciousness of the prince's past life, enter and inform the body of a cobbler as soon as deserted by his own soul, everyone sees he would be the same person with the prince, accountable only for the prince's actions...

Book 2, Chapter 27, 15

Are you your body? Are you your brain? Are you your soul?

Locke thought you were none of these.

He reflected about the nature of a person using a variety of “thought experiments” or brief stories. In one of his most suggestive stories, Locke imagined that a cobbler dies and after his death, the consciousness of a prince enters the cobbler’s body.

This person remembers all of the prince’s past experiences and none of the cobbler’s. We would say that the prince now occupies the body of the cobbler. So you are not your body or even your brain.

Locke concluded that what makes you the same over time is your continuity of consciousness and your memories.

Image credit: Cliff Landesman

Audio commentary

Listen to audio commentary by philosophers Tim Crane and Peter Millican, with Locke's words read by Victoria Jenner.

Download the accompanying transcript for the personal identity audio commentary (Word document)

Acknowledgements

This display is generously supported by the Polonsky Foundation